- Home

- Features Index

-

Features

Features

Uncovering Brain Intelligence Through the Integration of Neuroscience and AI

2025/12/26

What happens in the brain when living beings—including humans—learn, think, and make decisions? Professor Hiroshi Makino of the Department of Physiology is working to unravel these mechanisms by combining neuroscience and AI, using both theoretical models and experimental methods. While conducting neuroscience research at universities in the UK, US, and Singapore, he recognized the potential of AI and began forging his own path in the field through self-study. Since joining Keio University School of Medicine in 2024, Prof. Makino has also developed an interest in psychiatry. We spoke with him about the current frontiers and future prospects of neuroscience integrated with AI.

Pioneering a New Field by Merging Neuroscience with Self-Taught AI Skills

If Prof. Makino’s research were summed up in a single word, it would be “knowledge.” His work seeks to uncover what happens in the brain when humans and animals make decisions, using mice and AI.

“In our research, we record neural activity in the brains of mice as they perform tasks, using techniques such as calcium imaging, electrophysiology, and optogenetics. For example, we examine what changes occur in the brain when mice learn a task.”

The human brain contains about 86 billion neurons, and even a mouse brain has around 71 million, so pinpointing specific neural activity is no easy task. To address this, Prof. Makino constructed a theoretical model of neural activity using AI. He has conducted research comparing neurons in mouse brains with those in virtual AI brains.

“Our research lies in a cross-disciplinary field that integrates neuroscience with AI. Specifically, we use a method called deep reinforcement learning, which combines deep learning with reinforcement learning. Unlike other machine learning methods, deep reinforcement learning doesn’t require pre-labeled training data; the AI gathers and learns from its own experience. Since the method originated in psychology, its compatibility with neuroscience was already known. Still, no one has directly linked it to mouse brain neurons the way I have. While it has now been widely adopted, I believe we played a pioneering role in this field.”

Fascinated by brain science from a young age, Prof. Makino enrolled in a university in Scotland shortly after finishing high school. Despite building a well-established career as a neuroscientist, Prof. Makino then decided to teach himself AI entirely from scratch. A turning point came in 2015, when he was a postdoctoral researcher at a U.S. university and happened upon a DeepMind paper on deep reinforcement learning—it made him want to try it himself.

“I’m completely self-taught, but that’s the great thing about computer science—anyone with a computer can start learning. The materials are available online, and with enough motivation and some English ability, you can start right away. In contrast, neuroscience requires hands-on experiments, so it’s much harder for computer scientists to learn neuroscience afterward. I think the path I took was the right one for this kind of research.”

Observing Neural Activity in Mice as They Solve Tasks

In one study, mice were first trained to perform two separate behaviors. They were then given a task that required combining those behaviors, and their neural activity was observed as they solved it.

For example, one task had the mouse operate a joystick to bring a water spout closer so it could drink. In the preliminary training, the mice spent several months learning two things: that operating the joystick would result in getting water, and that they could lick the spout when it was available. The final task combined those two learned behaviors. The mice in the experiment were able to complete the task in under a minute.

“It’s difficult to define intelligence, but one possible aspect is generalization—the ability to apply learned knowledge and skills across different contexts. The mice were able to quickly solve a new task by combining the two skills they had learned.”

“In this experiment, we observe the activity of hundreds to thousands of neurons in mice, one by one, as they solve a task, using a technique called calcium imaging, which visualizes changes in calcium concentration through fluorescence when neurons become active. This allows us to observe the neural activity of living mice while they move freely.”

“In our experiments with mice, we examine the differences in neural activity between the pre-training phase and the moment they solve a new task. We believe that the mechanisms of cognition are at work in those differences.”

Observing Activity in the Virtual Brain of an AI Agent

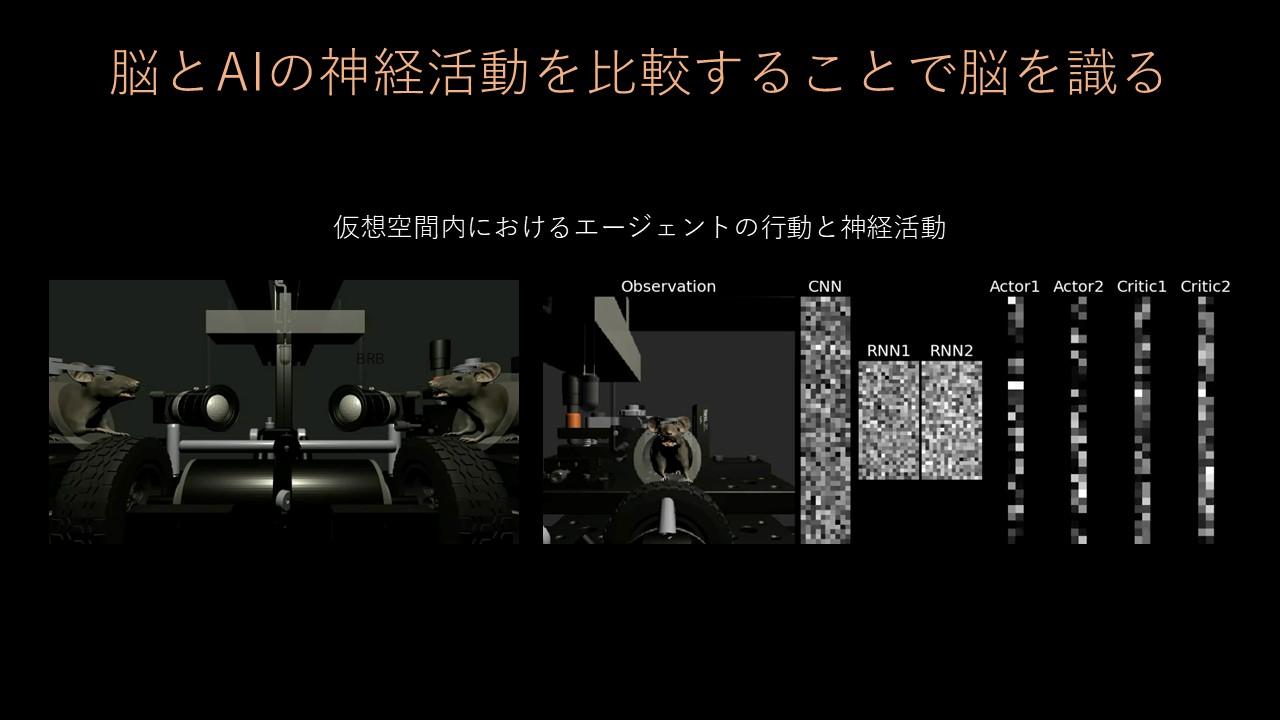

In this study, Prof. Makino also observed the "neural activity" of AI agents—autonomous systems that make decisions and take action—as they perform tasks, just as he did with mice. In the AI model, he defines a value function—specifically, an action-value function—that encodes rules such as, “In situation X, choosing action Y results in a reward.” He then has the AI perform the same task as the mice in a virtual environment and observes how its artificial neurons behave.

“With mouse neurons, it’s often difficult to explicitly determine what each activity represents. But in AI, where the neural networks are clearly defined, it’s much easier to identify each function and link it to behavior. So if we observe similar patterns in both AI and mouse brains, we may be able to interpret the mouse’s neural activity in the same way.”

Prof. Makino’s integration of neuroscience and AI deepens our understanding of brain function while also advancing the intelligence of AI systems.

“In my research, I use AI agents as theoretical models of neural activity, but as the work progresses, I often find that what works with mice doesn’t necessarily work with AI. By identifying and narrowing the gaps between AI and biological systems, we can help improve AI intelligence and, in turn, contribute to the advancement of neuroscience. Creating this kind of positive feedback loop is also one of my goals.”

Modeling Social Behavior in Groups of Mice

Prof. Makino has also studied decision-making in social and group contexts. In one experiment, two mice had to spin a wheel simultaneously to bring a water spout closer so they could drink, requiring them to cooperate.

“In these experiments, we examine how mice make decisions in relation to others—looking at neural activity in brain regions responsible for higher-order functions, along with dopamine release in what is known as the reward system.”

In the AI version of the experiment, two AI agents—each equipped with its own neural network—perform similar tasks in a virtual environment, and their neural activity is visualized.

“While the basic research method is the same as with a single subject, I hope to expand this work to study social behavior and group dynamics more deeply. When three or four mice are made to compete, one mouse consistently emerges as the winner. Mice also show an awareness of social hierarchy and will sometimes yield rewards to mice they perceive as being higher in rank. I want to examine the neural activity involved in these types of decisions, through both mouse experiments and AI models.”

Leveraging Keio’s Strengths to Simulate Human Society

Since becoming a professor in the Department of Physiology at the Keio University School of Medicine in 2024, Prof. Makino has taken an interest in human-focused medical research that is more closely aligned with clinical practice.

“The close connection between basic and clinical departments at the Keio University School of Medicine allows for active collaboration, and I’m currently discussing joint research on psychiatric disorders with the faculty in the Department of Neuropsychiatry. As a first step, I’m exploring whether AI models can be used to simulate human society in a virtual space.”

Around the world, researchers are developing virtual environments populated by large numbers of AI agents to simulate social phenomena, behaviors, and decision-making within those societies. In the kind of virtual society Prof. Makino envisions, some AI agents may experience social isolation through their interactions and relationships, just as humans do.

“For example, I’d like to explore what kinds of social factors might support recovery in individuals with mental health conditions. While this kind of research may fall more within the realm of psychology or cognitive and behavioral science than neuroscience, I’m encouraged by the fact that Keio University School of Medicine has several experts in those fields as well. As in my previous work, I plan to conduct experiments with mice and apply the findings to AI models in order to refine the virtual environment. Ultimately, it would be fascinating to simulate social structures that individuals perceive as conducive to happiness within a virtual space.”

This might also involve investigating advanced treatments and the mechanisms of new drugs being developed by the Department of Neuropsychiatry at Keio University Hospital, and using AI agents or animal models to examine which patient profiles and social environments they are most effective in.

Broad Knowledge and Experience Form a Strong Foundation for Researchers

When asked what students should focus on if they hope to study at the Keio University School of Medicine or pursue a career in medical research, Prof. Makino emphasizes two things: the ability to communicate in English with a diverse range of people and the importance of building a broad base of knowledge and experience that can later be integrated.

“I personally have worked to pioneer a new research field by combining neuroscience and AI. Diversity is increasingly emphasized in today’s society, and on an individual level, a wide breadth of knowledge and experience is a real asset.

In sports, for example, children in Japan are often encouraged to focus on a single sport from an early age, while in Europe and the U.S., they’re encouraged to try as many different sports as possible when they’re young. Research in AI and other fields has even shown, theoretically, that this approach can lead to better performance later when they specialize.

That said, few researchers actually manage to follow this approach. There are times when deep focus on a single area is necessary, but I hope people stay curious and engage with as many different things as possible.”

Reflecting on his future, Prof. Makino says that, as a researcher, he hopes to contribute to society in a meaningful way. In recent years, AI research has been largely driven by major corporations, which advance development at an astonishing pace using massive funding, making it increasingly difficult for academia to produce research with global impact. Still, Prof. Makino believes that with the right idea, it’s possible to carry out research that benefits both individuals and society at large. He sees his appointment to the Keio University School of Medicine as a valuable opportunity, and plans to continue breaking new ground in his research.

Hiroshi Makino

Professor, Department of Physiology

Keio University School of Medicine

Professor Makino graduated from the University of St Andrews (UK) in 2005 and earned a Ph.D. in 2010 from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (US). After serving as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, San Diego, and later as an Assistant Professor and principal investigator at the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, he assumed his current position at Keio University in 2024. His main areas of research include neuroscience and artificial intelligence.

*All affiliations and titles listed are those at the time of the interview.